Are we addicted to face filters?

Everywhere we look online, we’re inundated with images of perfect faces and bodies. The eponymous Instagram face—that augmented face defined by catlike eyes and high cheekbones—is unavoidable. But the trend is not restricted to Instagram: edited faces proliferate across the web.

That’s because achieving the look has never been easier with the emergence of augmented reality (AR) face filters, which smooth our complexions, lengthen our eyelashes, and simply make us look like enhanced versions of our own selves.

While most of us know the images produced are not “real,” they continue to shape our sense of beauty. Even if we’re secure and comfortable in our own skin, augmented faces are still changing the way we view ourselves and how we view others.

The level of conscious recognition behind that is debatable: do we see filtered faces and think specifically “I want to look like that,” or is it just changing our concept of beauty subtly, without us consciously noticing the shift in our expectations?

It’s time to explore why face filters have become so pervasive, and how they are, in fact, changing us–whether we realize it or not.

How social media enables us

Both Instagram and Snapchat offer augmented-reality facial filters on their platforms. Some are cute and innocuous–like adding dog’s ears and a long floppy tongue–while others are designed to simply make us look better. The idea is to achieve your “ideal” face and tweak your way to perfection.

Young women tend to be the biggest users and the most susceptible to the pressure to filter, with over 90 percent of British women aged 18 to 30 reporting having used an AR filter to improve their appearance at least once.

Unfortunately, the problem is only escalating and was compounded by the onset of the pandemic, in which editing apps like FaceTune saw usage increase by 20 percent. As we spent more time online, we were busy crafting very specific versions of ourselves to present to the world. We saw ourselves more online, uncomfortably staring back at our own faces on Zoom, and put additional time and investments in curating selfies.

It also doesn’t help that many infamous celebrities are upholding the trend. Even Kylie Jenner, who has spent millions on altering her physical appearance and has all the world's resources at her disposal, has been publicly critiqued for editing her pictures. If billion dollar celebrities with plastic surgeons at their beck and call still feel compelled to edit their photos, what’s that mean for the rest of us? Moreover, what’s mean for the young girls consuming that content and feeling they must match it?

Addicted to the feeling

So, face filters have become ubiquitous, transforming what started as a gimmick with friends to something of a necessity when posting. It’s not just the fact they’re popular, but that they’re feeding into social media’s impact on our neurotransmitters, or the body’s chemical messengers.

Multiple studies have shown likes on social media release dopamine, the feel-good chemical associated with rewards. The more likes we get, the more dopamine released, making us physically addicted to that feeling and desperate to reactivate those reward pathways again.

Even former Google employees have admitted to engineering social media in order to produce the same reaction as gamblers at a casino. It’s a predatory and addictive industry that intentionally keeps its players hooked, or desperate to keep up the content creation game to gain likes and attention.

And you know what’s a sure-fire way to increase likes? Looking your best, even if it’s not really you, because looking conventionally attractive feeds into the algorithm. And the more successful the post is, the more likely we are to do it again, creating a toxic cycle of positive reinforcement.

So, while it seems sensationalist to say, it’s a fact: Instagram is rewiring our brains. It’s getting us hooked by releasing certain chemicals, causing surpluses and deficits of various neurotransmitters, and shifting our expectations: expectations for relationships, for beauty, and for ourselves. It’s making us validation addicts.

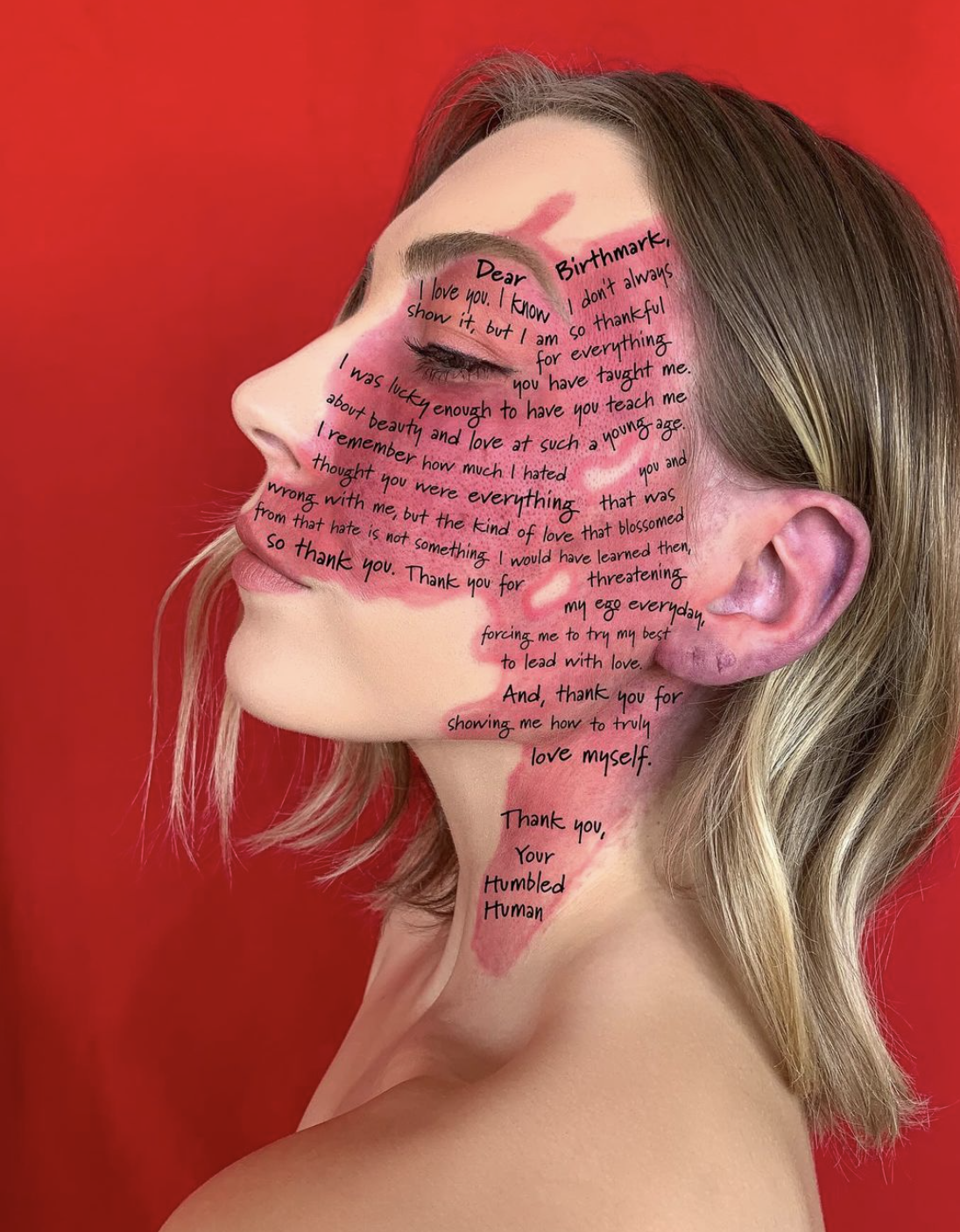

Beauty is not uniform

When discussing how Instagram face is shaping beauty standards, it’s important to note that every culture has its own ideal of beauty, whether it’s fair skin or a bronzed tan, bouncy curls or hair straight as an arrow.

You’ve probably seen that infamous photoshop experiment, in which graphic designers from around the globe were asked to photoshop the same image of a woman to meet their country’s ideal standard of beauty. As you can imagine, the results were quite mixed.

That’s because there is no one size fits all definition of beauty; rather, diversity is beautiful. Unfortunately, the Instagram face phenomenon is only pushing us further towards homogenized, largely European ideas of beauty.

The Instagram face trend has been said to “deracialize” us, because it’s somewhat racially ambiguous: but it’s still clearly light-skinned and thin. And the impact it has left in its wake is an absolute mess: unrealistic beauty standards shaped by European preferences.

Now we’ve even taken those beauty standards and amplified them, beyond tweaking images of actual women to creating images of women who aren’t real at all. Simply look at the results when an AI bot is directed to generate images of stereotypically attractive women (once you can get past the seven hands and mangled fingers; AI still can’t quite get hands right). The fake women in the AI images all share the same features: white, thin, blonde, and hot.

But they’re not real. None of it is. Remember that.